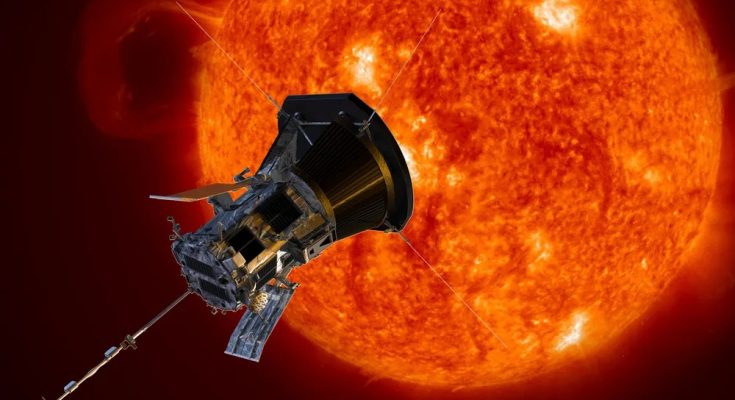

The holiday season is a busy time for humankind’s sun-surfing spacecraft. This Christmas Eve, the Parker Solar Probe will be going where no probe has gone before: a mere 3.8 million miles from the sun’s surface.

Around 6:53 a.m. Eastern time on December 24, it will pass the closest that any spacecraft has ever been to our roaring sun. And it will do so in another record-breaking fashion: traveling 430,000 miles per hour—the speed equivalent of traversing from Washington, D.C., to Tokyo in under a minute—making it the fastest human-made object to ever zip across the universe.

“It’ll be inside the upper atmosphere of the sun, literally touching the star,” Nicki Rayl, NASA’s deputy director of heliophysics, tells Julia Jacobo and Mary Kekatos of ABC News.

Temperatures at that distance from the sun will reach 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit. But the Parker Solar Probe is well equipped to handle its latest trial by fire. To avoid the fate of the mythological Greek figure Icarus, the spacecraft comes with a heat shield that will keep its sensitive instruments just above room temperature, at roughly 85 degrees Fahrenheit.

This 4.5-inch-thick protective layer was a decade of research in the making. A water cooling system, layers of insulating carbon foam and a bright white ceramic paint coating to reflect the worst of the heat all give the probe its equanimity in the face of the sun’s glare. During field tests in the lab, the heat shield was designed to withstand temperatures up to 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit.

Launched in 2018, the Parker Solar Probe was designed to study our temperamental sun, specifically its solar wind activity that’s known to disrupt satellites and jam up telecommunications on Earth. Scientists hoped it could answer some key questions about our nearest star, per CNN’s Ashley Strickland, including why the sun’s outer corona is hundreds of times hotter than its surface and how particles of the solar wind are generated.

Close approaches, known as perihelions of the probe’s run around the sun, are valuable opportunities to view the sun’s ethereal corona up close. The corona is the cauldron where coronal mass ejections lick into existence, but it can’t be seen from Earth except for during a total solar eclipse. Flying through this outer layer will allow the probe to collect data needed for understanding the sun’s pulse and predicting space weather.

“No human-made object has ever passed this close to a star,” Nick Pinkine, Parker Solar Probe mission operations manager at the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University, says in a statement. “So, Parker will truly be returning data from uncharted territory.”

Slightly larger than a golf cart, the solar probe is too puny to ferry enough fuel for its entire seven-year journey. Instead, it got a speed boost from Venus in a maneuver known as a gravity assist. Slingshotting around the second planet—seven times in all and most recently in November—allowed Parker to bend its trajectory toward an orbital flight around the sun. As the probe swung around Venus, it also collected data on the planet’s own scorching atmosphere.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/53/b4/53b41340-5a3a-444a-b3ec-bf33e5e54594/wispr_venus_image.webp)

The timing of the probe’s solar arrival will be fortuitous. Currently, the sun is undergoing a solar maximum phase, an explosive peak in an 11-year cycle of activity that will extend into 2025. During this frenzied period, the sun’s magnetic poles will flip, sunspots will bloom across the face of the star and it will increase its firepower, hurling ionizing radiation toward the far reaches of the solar system. These flare-ups can stir up powerful geomagnetic storms on Earth. In mid-May and October, the sun threw such fits that the northern lights were visible all across the continental U.S. and as far south as Florida.

Since its launch, Parker has made 21 close approaches to the sun, the first being in 2021. This upcoming, 22nd rendezvous will be its closest yet. Before this spacecraft, the last record holder was the Helios 2 spacecraft, which in 1976 came within 27 million miles of the sun. Parker outdid that number on its first flyby; now, the newer probe will be seven times closer than Helios 2 came. It will make only two more close approaches on March 22 and June 19 next year at a similar distance to this skim, before calling it quits for its seven-year primary run.

What the Parker probe has gathered about the sun so far has already revolutionized astronomers’ understanding of our planet’s celestial host. It has discovered streamers of material that wrinkle the sun’s corona and observed magnetic funnels emerging from giant bubbles on the sun’s surface.

As thrilling as Parker’s newest encounter will be, Earthlings will not get to follow its action live. Scientists will not be able to contact the spacecraft as it flies through perihelion, so they’ll be in the dark until Parker beams back its status on December 27. That signal will only be a check-in about its general health—researchers will have to wait until the new year for Parker to transmit back its first data on this latest exploit